Identity & Image

Finding Vivian Maier: Gently Resisting Immortality

“Photography was a license to go wherever I wanted and to do what I wanted to do.” —Diane Arbus

[spoiler alert - this essay reveals details of the film Finding Vivian Maier]

The instant a photograph is made it defies time/space. The linearity of being alive is gone in an instant as the aperture closes down and image is imprinted, chemically or digitally. It’s an act of jouissance really, whereby the moment the photographer snaps the photo le petit mort is realized. The act of photography is a mechanical attempt at reproducing ecstasy. Capturing that which is ineluctable, illusive and impermanent. Melding the moment of being with the past and future simultaneously. In its jouissance it is fumbling towards identity, hoping to understand the fleeting present by capturing it eternal.

“The more of each photograph, its auratic power and animism, runs precisely on the excess of each beyond artifice and explicit content that is a consequence of the combination of the camera’s mechanic looking and the proliferation of images, each being part of an indefinitely long series.”1

The enigma of Vivian Maier is her contradiction in being a photographer— being in this world and interacting with her surroundings, photography her mediator, and consciously avoiding the outcomes of the mediation itself. Her’s was perpetual self inflicted tease, never fully having the courage to fully realize that living means death by a thousand tiny cuts.

Finding Vivian Maier is a documentary by John Maloof and Charlie Siskel that tells the accidental discovery of a treasure trove of film and personal effects by an unknown photographer, Vivian Maier. Maloof discovered the first boxes of black and white negatives at an auction in Chicago while researching a historical book on Northwest Chicago. Maloof’s obsessive character and his historical-detective instincts led him to trace the origins of the negatives he found based on an address he found amongst them. He traced the address and found the caretakers of her estate, old employers whom she worked for as a nanny. Eventually, Maloof uncovered more than 100,000 negatives in black and white in color spanning decades beginning in 1949, along with letters, tchotchkies, her Rollieflex camera and even rolls of Super 8 film. The result has been a treasure trove of impressive work that nudges at the coattails of greats like Robert Frank, Arthur Fellig (Weegee) and Diane Arbus.

Maier while alive, never showed her work professionally. Only a smattering of images were ever printed. Born in New York City, she ended up spending the balance of her life in the northern suburbs of Chicago, working as a nanny for a series of wealthy families. She even worked for Phil Donahue in the 1970’s. She remained in northern Chicagoland until her death in 2009. Her work as caretaker and surrogate mother to well-to-do Chicago families afforded her both the security and flexibility she desired to pursue her photography. Her daytime childcare often included adventures into the inner city of Chicago, children in tow, shooting the seedy underbelly of the city and its downtrodden occupants.

Maier’s had a gifted eye for human nature, particularly in the early black and white work. The contrasts between light and shadow mixed with her fascination for urban street life gives her work an energy that is often absent modern street photography. Although the full oeuvre has yet to be revealed, it is clear at the moment, her early work from the 1950’s and early 1960’s in black and white was her strongest. The contrast between her suburban, wealthy neighborhood and the bustling, ragged streets of Chicago gave her photography an emotional content that runs deep. There is little doubt that had she pursued professional representation she would have been well received if not heralded as a contemporary of the greats of that period, like Frank, et. al. Maier instead chose to be reclusive, mysterious and antisocial. She hoarded objects, newspapers and film for years with a purpose she took to the grave. She never pursued any public recognition and stored her observations away in boxes, transporting them from place to place until they wound up in a mini storage unit after her death.

The character of photography, especially street photography, as an art is beholding to collective memories and our desire for connection. We look at photographs in our present world knowing all of them reference some past. This creates an automatic nostalgia. The great photographers negotiate this inherent quality of photography by embracing the sublime or creating their own deliberate, imposed narrative onto the images, no matter how candid they may appear. Maier’s work follows in the footsteps of Walker Evans who made photojournalism an art form. This places her work both in alignment with the art form and at odds with it due to her lack of exposure or professional attitudes toward the practice. The draw of Maier’s work is a dialogue on poïesis, whereby her identity and existence was contingent upon the poetry of making. She didn’t care about an audience because her photography was an act of alterity which reaffirmed her identity daily.

“The experience of of a photograph is associative and simultaneous, and in this respect it resembles our experience of poetry. In poetic writing, meaning is not achieved by means of a consistent structure of controlled movements along lines made up of sentences. Rather, the pen is made of lines that may resemble sentences typographically but which abrogate the requirement to be read the way sentences are read. So there is a break with any necessary relation to the chronicle.”2

I find myself enamored and troubled by Maier’s work. Her fixation on the downtrodden and destitute demonstrates an allegiance to the cause and her unwillingness to actually be present in that world. She remained safely tucked away in her suburban enclave while her daytime exploits made her a poverty tourist and a hypocrite. This doesn’t diminish the power of the early work, but it may explain an ultimate weakness as an artist. Weegee worked for years as a newspaper photojournalist living in the heart of his native NY. Frank traveled through America as a Jew, family in tow, traversing the deep south at a time when Jews were as equally despised as African Americans. And Arbus, befriended the strange and wonderful people she encountered, perhaps even to a fault, given her eventual demise. Maier on the other hand remained aloof, a perpetual visitor but never a full inhabitant.

The film raises a question regarding her mental health, which feels like a conceit to push the artist-as-eccentric frame. The terms recluse, hoarder and mentally ill are tossed around throughout the film to describe her perceived state of mind. She exhibited borderline autism given her social anxieties and need to keep her art hidden from view and her desire for privacy, often inventing fake names or no name at all. However, I found the cliche’d tropes mentally ill, weirdo, reclusive artist, an injustice to her artistic drive and humanity. The contingency of serving as a nanny to wealthy suburbanites both enabled and seriously hampered her development as an artist. Having no community of her own to relate to she was imprisoned by the largely culturally empty community she served, raising children for people that had more money than time, so much so they entrusted the raising of their children to an eccentric photographer. Had Vivian been introduced to a few like-minded artists, no matter her dispensation for isolation, she might have found a pathway to sharing her work with a larger audience, and sadly, enabled herself true freedom from the suburban confines.

The question arises of outsider art in Maier’s work, which may be in part, the reason institutions are currently resistant to analyzing her images or including them in their collections. What is of greater concern to me, is not whether she pursued a dedicated exploration of her craft—meaning the usual public exposure which in turn provides a dialogue back to the artist, but rather her lack of depth. After watching the movie I spent a considerable amount of time looking at her work online and what is striking is the absence of work later than 1980. The work that is visible shows a recognizable decline in its content as time passes. This I think, is a result of her lack of exposure to any peers or audience. Without a foothold in reality she was left to replicate the same narrative over and over again with few fresh insights. The power the work holds in its early stages, 1950 to 1975 is due in large part to the freshness of her eye, her personal energy and the content of what she was capturing. To audiences of today, the rediscovery of a time when the clothing and culture were so fundamentally different, has a nostalgic power that captivates far more than perhaps anything she may have shot during the 80’s or 90’s. As personal technology has become ubiquitous, so has the homogenization of our culture. The differences and fractures between our various players in American society are less evident than they used to be. The homeless are ushered out of cities into camps, largely out of view of the average citizen. The vibrancy of individual merchants has been replaced by the uniformity of chain stores. The expectation that a suit or dress of a certain caliber as the baseline for public dress has been subsumed by hoodies, jeans and Keds. Sitting in a 3-star restaurant in San Francisco or New York, you can no longer distinguish the multimillionaires from the middle class. In Vivian Maiers more powerful photographs, this milk toast America was largely absent. In fact Maier seemed to revel in the contrasts between fur coat cloaked elite and one-eared bums.

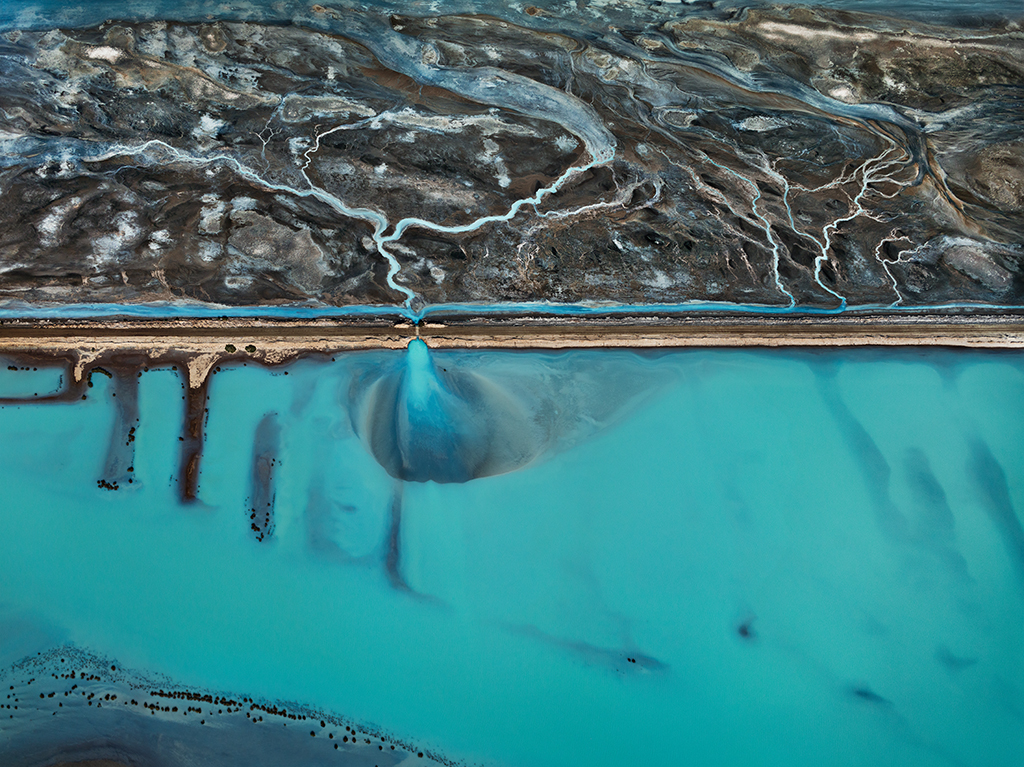

Herein lies the rub with Maier’s work. There is an increasingly coldness and distance that seeps into her work as time passes. Even in the limited body that is available for viewing online, it is apparent that certain staged themes and ideas are replicated with no new ground being broken. Her color photography has a gentle beauty in its naiveté but seems not to mature. Maier is not a colorist for sure, certainly not in the way William Eggleston or Jeff Wall are. All artists need an audience to grow and the lack of this is apparent in Maier’s work. It’s ironic that a woman so fascinated by the world around her was so resistant to participating in it.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2o2nBhQ67Zc&w=560&h=315]

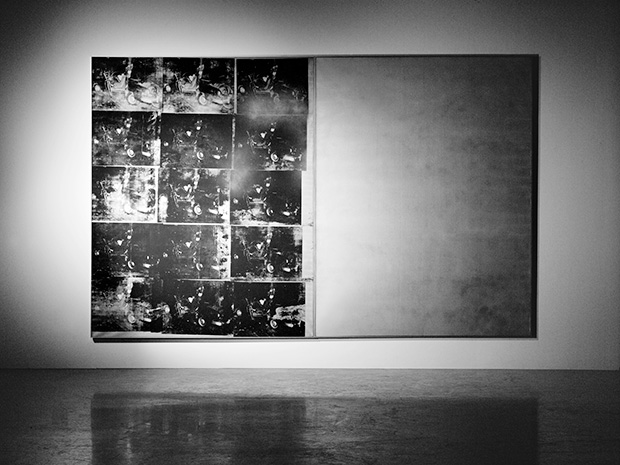

The film repeats the question of an artist’s worth in relation to their own gained immortality. Some artists take on immortality as a quest, continually working with a long-term view that each work will sit within a larger, collected body retrospectively analyzed postmortem. Others simply work for works sake. As William Eggelston has said, “Photography just gets us out of the house,” The making, being the end to a means, not the other way round. Whether Maier was the former or the latter matters not because she’s dead and it bears no real meaning to the work itself. If Maier’s work becomes part of the important 20th century photographic canon it will be because it adds to the historical conversation or given our current art market, because someone deems it equal to the hoarding of gold or diamonds. Time will tell, whether or not that holds true but one thing is certain, Vivian Maier will not have a say in her own immortality.

Having witnessed a plethora of art at this stage in my life I can tell you unequivocally that Vivian Maier is certainly worth visiting with. She’s stronger than most photographers ever become and despite her shortcomings there is a magic in some of the photos that will hold you breathless. I’m glad her images avoided the landfill and I’m glad for Maloof’s persistence.

1. J. M. Bernstein, Against Voluptuous Bodies, Late Modernism and the Meaning of Painting. p. 276

2. Jeff Wall, Selected Essays and Interviews: Monochrome and photojournalism in On Kawara’s Today Paintings. p. 138