Hots on for Nowhere

The moon and the stars out of order As the tide tends to ebb and sway The sun in my soul's sinking lower While the hope in my hands turns to clay I don't ask that my feet fall on clover I don't roam at opportunity's door Why don't you ask my advice, take it slower Then your story'd be your finest reward*

The intent of this blog has always been to give some context to contemporary art and cinema so that those who are unfamiliar with the devices and methods used by artists might scratch at the surface of a deeper truth. Today I am thinking of Warhol’s early mastery and its parallel to the state of our nation because a personal loss mirrors this larger idea and because as stated earlier, art can be a bridge between the intimate and the universal. It is not the loss itself, as much as the circumstances that led to it that bring me such frustration, anger and ultimately, understanding. To witness the dynamics of our broken American psyche at play on a very personal scale is truly difficult.

Watching someone squander their life because they cannot comprehend the preciousness of it, is almost more painful than having them die. Their perpetual delusion of materialism was thought to make them happier. Their inextricable connection to immortality through their pursuit of such delusions ultimately cost them their life. What could doctors and medicine offer that a new purse or a shiny set of nails couldn’t? How could eating properly and exercising possibly measure up to a visit to the hair salon and a brand new iPhone? Why should one worry about protecting your children in settling your affairs after death if one is never going to die? These were the delusions of my mother who died recently. She carried them all through her life as long as I can remember. However, the finality of death has caught up to her despite her magical thinking and I’m hoping it might serve as a lesson for others in their living.

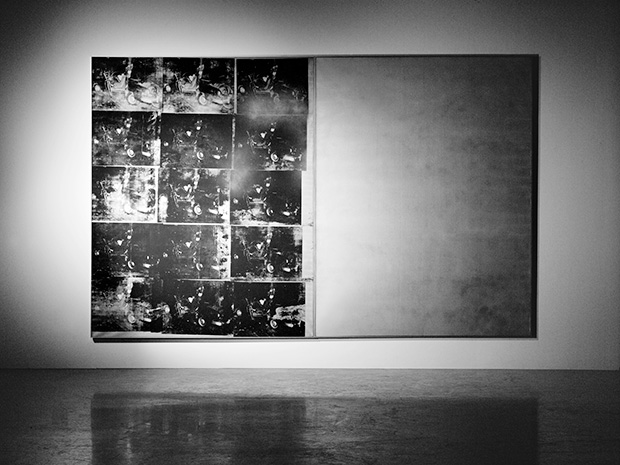

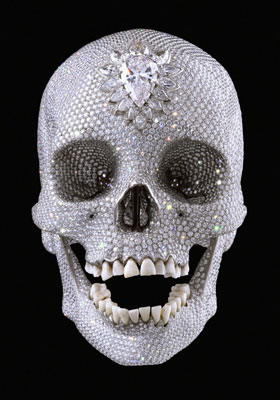

We are a culture possessed by dreams of immortality and armageddon. We live at the outer limits of sustainability, persisting a dream of ever more, (and more still) all the while knowing in our heart of hearts that eventually the clock will run out on our unending consumptive cravings. Americans hold death firmly in the abstract, which is odd given our abhorrent reactions toward abstraction in general. It’s a shame really that Andy Warhol is not still alive as he might have been the one to invent For the Love of God, instead of Damian Hirst. It seems out of place for a Brit to have invented it, or shall I say, stolen the idea at least. A diamond encrusted human skull seems much more befitting of the cultural delusion persisted in America and American art. Warhol’s success after the Campbell’s soup cans was solidified with his recognition of our American duality in one of his few inspired moments, Silver Car Crash. The large silkscreened canvases of hideous car crashes didn’t just echo the appropriated newspaper spaces of Jasper Johns but elevated them to a confluence of Johns work and Pollocks. The 70 some paintings Warhol created in 1963 to 1964 often referred to as his Death and Destruction Series leveraged imagery using photographs of gruesome car crashes, electric chairs, and suicides. This was Warhol’s apex and he would never make work this good again.

It is not enough to make the viewer aware of death, horror and tragedy, an artist needs to couch that realization in the cultural zeitgeist. What makes Warhol’s Car Crash paintings so good is not what you see, but what you don’t see. The two paneled paintings are nearly 9 feet tall and 13.5 feet wide—monumental scale. In the Car Crash paintings, Warhol depicts what Sartre referred to as the For-itself itself, that hoped for synthesis of being and nothingness. The idea that through art and the allegiance of beauty and death, one could find a cohesive consciousness, a bond if you will, between one’s imagined being and the reality of living. Warhol’s diptychs present themselves in art historical reference as a new kind of religious iconography depicting the union between acknowledging the inevitability of death and the obliqueness of oblivion united in the marriage of aesthetic truth. Here Warhol was informing us of a pathway America was on that showed how we might hold the contradiction of our own consumptive powers in balance with a greater truth, an almost holy other. No doubt his catholic upbringing paired with his own blasphemous lifestyle, must have contributed to his awareness of living contradictions, at least subconsciously. The coldness and mechanization of the silkscreen as a riff on mechanical reproduction was blended with bright colors or silver paint demonstrating our tendency toward celebrity and advertising, something Warhol knew a great deal about. This was the American dream of having it all. America was inventive, powerful, and vulgar in its tastes and yet we could produce great genius, art and land men on the moon (although not at the time of these paintings).

Unfortunately, Warhol’s fantasy which was America’s fantasy was just that, false. Sustaining the duality has cost us dearly as we are slowly seeing our status on the world stage diminished and our economic model collapsing, whether we want to admit it or not. The fictive model of eternal ever greater consumption as aesthetic ideal has congealed into a self-replicating ironic loop of ever more crass, unimaginative pathos. America is an impotent giant torn between 21st century possibilities and 6th century conservatism. Our consumptive power has become a virus that now eats the young of America, consuming their potential and our hope for any form of real future democracy by fixing their gaze upon corporate brands rather than citizenship. It turns out the right-hand panels of Warhol’s work, the one’s mirroring the void turned out to be the more powerful. We lost our sense of balance because we lost our ability to hold those two ideas—death and being—as an ideal. Our denial of death as a concept through worship of celebrity iconography, and blind consumption have left us ontologically impotent.

I am not a believer in the afterlife. I do not believe in reincarnation or heaven or whatever you want to call it. I believe we are all born of stardust and end as stardust. Matter is perpetual as far as we know it and infinite in its own right. Believing in this infinity has given me clarity and purpose about my own life. It humbles me and it has allowed me to understand things on both a macroscopic and microscopic level. I am susceptible to desire and consumption as much as the next person from time to time, but I do not fear death. I love whatever sense of consciousness I hold in this moment as I write these words but I know in many respects it is a kind of illusion that given enough weight can fool us into believing in our own immortality. Warhol’s Crash paintings must live as a diptych because the panel that represents the void is the true reminder of death, not the hideous filmstrip silkscreen of the car crash itself. Tragedy, happiness, sadness and all of the emotions must be held in check by the understanding that we all die. Seeing death, especially our own death and holding that image clearly, without fear, gives us a presence to make wiser choices about living. Consumption becomes less important when you realize you have only so many days on this earth in your current conscious form.

Warhol’s Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) will always hold a lasting impression on me, not merely because of its brilliant portrayal of American duality held in check, but because it was painted in the year of my birth. It is an iconic gesture that I can hold as both a universal symbol and a personal one. It reminds me that no amount of money or things can replace my health or ability to share my creativity with the world. Paintings are an aesthetic mirror held up to our culture that shows a way toward balance. I may now be an orphan at 50, but the lesson I choose to take from this loss is to hold steadfast in my acceptance of death and to live and love as much as I can until I make my way back to stardust.

R.I.P. Diana Dowd Greene, 1941 - 2014

* Hots on for Nowhere, Page/Plant, 1975 - off the album Presence by Led Zeppelin.