Anarchy & Order

Musings on the state of beauty and the sublime.

“Beauty is your sure bet that desire, unmolested, is going to make you feel around. The Sublime is your failure to feel anything around the beautiful, knowing well it’s there.” —Faheem Haider

“Reports that say there's -- that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things that we know that we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we don't know we don't know.” —Donald Rumsfeld, United States Secretary of Defense (2002)

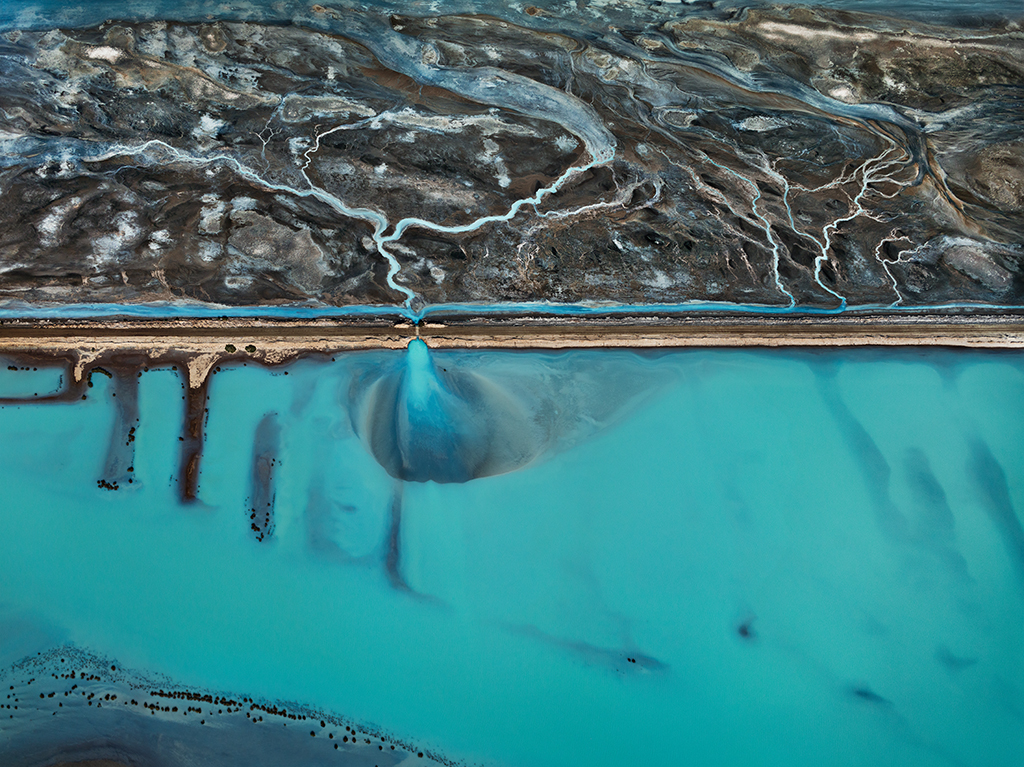

We are living in a time filled with visions of the apocalypse while simultaneously denying its near eventuality. Climate change is upon us. Officially or not we’re firmly seated in the Anthropocene. We will not meet our demise by way of alien space craft, zombie invasions, thermonuclear war or even the Terminator. Instead we have started a war with the planet itself and that war will more than likely going to end poorly for the human race. The concept of the entire world’s climate changing, melting polar ice sheets, the release of trapped CO2 in the tundra and a shift in global weather patterns inevitably triggering irreversible changes is more than most human beings can wrap their minds around. This is the dilemma of beauty and the sublime.

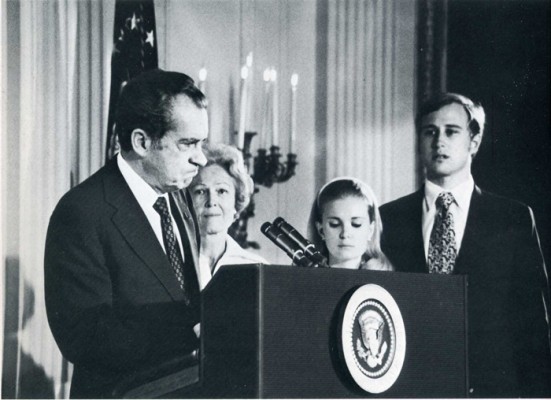

The assassination of John Lennon in 1980 and the inauguration of Ronald Reagan precisely a month later, marked the end of an era in American renewal. Ideals bound in the sublime, freedom chief among them. For a time we used our post-war prosperity to grow the cultural infusion we received prior to the war from those fleeing fascism. Lennon, another expat who chose to live in New York, was a symbol of what a culture might achieve when holding a firm grasp on the sublime. Reagan on the other hand, a Hollywood fantasy, preferred the Norman Rockwell portrait to the Pollock landscape. To Reagan any notion of the sublime was to be feared and freedom lived firmly in the real, not the abstract. Of course, that real was grounded in the tradition of rich, white men. Since then we’ve seen an accelerating erosion of abstract ideas and a continual, exponential embrace of certainty. This has led to a rise in fundamentalism, absurdist political frames like Ayn Rand Libertarianism, and a fanatical adherence to antiquated, dangerous ideas guaranteed to solidify the onslaught of climate change.

Beauty sits firmly in the Now of desire. It is tactile, emotional and lives within the boundaries of the body and our biology. The sublime fractures the Now, leaving us fumbling in the dark for the certainty of beauty. This dynamic which makes both concepts more powerful and recognizable, has been consumed by fear. The shiny culture of corporate production and our desire for the outcomes of that production—Nike shoes, BMW cars, the latest Beyoncé album—is now what stands in for beauty. It’s a deception. It has no place in the Now, only in the future. In parallel to consumerist beauty, and its replacement of democratic freedom, lies our idea of technological beauty. American fundamentalists drive automobiles and use smartphones that require a level of technological sophistication far exceeding their understanding. Yet they deny science because the science that led to the technology that provides them their comfort requires an embrace of the sublime that terrifies them far more than the certainty of an angry god.

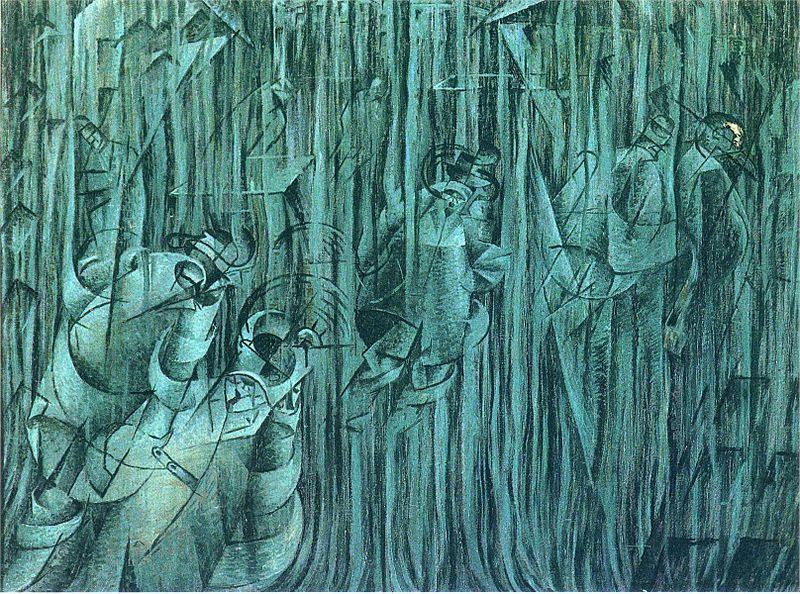

The cognitive dissonance between technology and religion is a failure of imagination. Art is failing us and as a result our imaginations a left to fester on memetic replications of layered ironies. The inside joke of regurgitated culture is the only idea persisted, with few exceptions. Our art isn’t telling any new stories. It offers no real form of beauty because it has no stomach for the sublime. Just as technology cannot exist without the pursuit of pure science, beauty cannot exist without the sublime. The unknown unknowns are critical in our dialectic as they lead to inquiries bound by deep imagination. Art production is bound by intellectual curiosity not by talent and right now we’re sorely lacking in intellectual-aesthetic curiosity. Artists aren’t interested in redefining art, they think art-making is simply burning down the house of aesthetics in and of itself. I’m specifically thinking of Richard Prince, Tracy Emin and a cadre of followers and mimickers who pretend at art-making because they offer no real dialogue between beauty and the sublime. Prince’s effete riffs on pulp fiction book covers and Marlboro ads took whatever integrity was left in Warhol’s dialogue and flattened it into a dull plane of aesthetic purgatory. The artists who followed like Emin, et. al. have merely punctuated the effort in a pedantic ballet of aesthetic scatology.

We need a new definition for beauty and aesthetics. We have long since outgrown Plato, Kant and yes, even Heidegger but we are left with no new outline. The sublime is narrowly defined by the fear of terror. The terror of 9/11 seemed sublime because our art has been so narrow, plastic and ironic for so long. There is nothing sublime about a president standing on rubble and encouraging people to get back out there and shop.

Our culture and our art is trapped in an adolescent understanding of beauty and the sublime. A true imagining of the sublime is to ponder what lies beyond the infinite, to be so overwhelmed by the breakdown of physicality and the Now, that we are paralyzed. We attach words to these experiences but they all fall woefully short—altered states, the uncanny, transcendence, the infinite—are all our weak attempts to add context to that which has none. The failing in this is its lack of recognition that the sublime is not ‘out there’ in the intangible ether, but lives inside all of us in the form of consciousness. The voice inside our head as we interact in the Now, fractures the nature of any form of tangible reality. As Daniel Dennett says,

“The salmon swimming upstream to spawn may be wily in a hundred ways, but she cannot even contemplate the prospect of abandoning her reproductive project and deciding instead to live out her days studying coastal geography or trying to learn Portuguese. The creation of a panoply of new standpoints is, to my mind, the most striking product of the euprimatic revolution.”

Grasping the infinity of available ideas is what makes us human.

Viewing images of the Hubble telescope’s view of the cosmos is an aesthetic experience that marries beauty and the sublime. The images of giant gas clouds millions of light years across our galaxy can be seen as physically beautiful. Recognizing the origins and time/space dimensions of those gas clouds disrupts their aesthetic value and seats them in the sublime. Our cultural cult of personality teaches us that beauty is precious, pretentious, and idealistic. The art world’s reaction to this admiration of the plastic-pretty with classical ugliness. A didactic and equally immature response to the current realities of our world. Entering the realm of the sublime gives shape to beauty precisely because it suddenly becomes precious against the abandon of the former. Art isn’t a response to anything, when it works. At its best it provides us a slim grasp of the Now in order to allow access to the infinite. Robert Hughes said it best during the apex of Reaganism,

Viewing images of the Hubble telescope’s view of the cosmos is an aesthetic experience that marries beauty and the sublime. The images of giant gas clouds millions of light years across our galaxy can be seen as physically beautiful. Recognizing the origins and time/space dimensions of those gas clouds disrupts their aesthetic value and seats them in the sublime. Our cultural cult of personality teaches us that beauty is precious, pretentious, and idealistic. The art world’s reaction to this admiration of the plastic-pretty with classical ugliness. A didactic and equally immature response to the current realities of our world. Entering the realm of the sublime gives shape to beauty precisely because it suddenly becomes precious against the abandon of the former. Art isn’t a response to anything, when it works. At its best it provides us a slim grasp of the Now in order to allow access to the infinite. Robert Hughes said it best during the apex of Reaganism,

“What has our culture lost in 1980 that the avant garde had in 1890? Ebullience, idealism, confidence, the belief that there was plenty of territory to explore, and above all the sense that art, in the most disinterested and noble way, could find the necessary metaphors by which a radically changing culture could be explained to its inhabitants.”