The Bleakness That Bonds Us

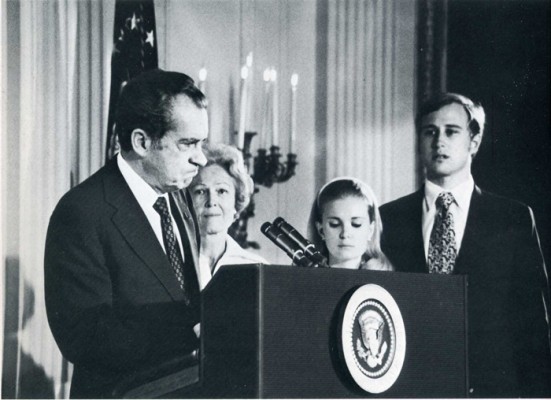

I am a child of Watergate. When I was in grade school in the 1970’s it was an all consuming subject, even among eleven and twelve year olds. My small town high school library made sure there was a special reserve section that dealt with the issues surrounding the continuing unfolding of the scandal and eventual disgraceful resignation of a president of the United States. As a adolescent the idea that a president would not only lie but manipulate the infrastructure of the U.S. government to win re-election was nearly impossible to swallow. My parents were products of the post WW II boom. They went to college to gain teaching degrees which our government paid for in order to promote a more robust democracy in the wake of the atrocities of fascism. It was a time of relative idealism despite the assignation of John F. Kennedy just three months after my birth and later Martin Luther King and his brother Bobby. It was a time of hope despite the insipid bombing of Cambodia, the knifing of a young man at Altamont during a Rolling Stones concert and the hideous plague rained down from the Manson family in L.A. The remnants of 1950’s America was still holding charge in small town America. I was taught even then, at that early age about civics, citizenry and the idea of a functional government. My father voted for Nixon, twice and my mother voted first for Humphrey than McGovern, but I was taught to respect differences because the vote is what enabled reconciliation. Republican government with democratic underpinnings was the greatest form of government known on Earth, and despite it’s faults, it was to be respected.

I am a child of Watergate. When I was in grade school in the 1970’s it was an all consuming subject, even among eleven and twelve year olds. My small town high school library made sure there was a special reserve section that dealt with the issues surrounding the continuing unfolding of the scandal and eventual disgraceful resignation of a president of the United States. As a adolescent the idea that a president would not only lie but manipulate the infrastructure of the U.S. government to win re-election was nearly impossible to swallow. My parents were products of the post WW II boom. They went to college to gain teaching degrees which our government paid for in order to promote a more robust democracy in the wake of the atrocities of fascism. It was a time of relative idealism despite the assignation of John F. Kennedy just three months after my birth and later Martin Luther King and his brother Bobby. It was a time of hope despite the insipid bombing of Cambodia, the knifing of a young man at Altamont during a Rolling Stones concert and the hideous plague rained down from the Manson family in L.A. The remnants of 1950’s America was still holding charge in small town America. I was taught even then, at that early age about civics, citizenry and the idea of a functional government. My father voted for Nixon, twice and my mother voted first for Humphrey than McGovern, but I was taught to respect differences because the vote is what enabled reconciliation. Republican government with democratic underpinnings was the greatest form of government known on Earth, and despite it’s faults, it was to be respected.

Then came Watergate. It was as if I learned that one of my uncles was a child molester or heroin dealer. I had no personal opinion about the president, but the mere fact that the leader of the free world could lie under oath and deceive on such a large scale was nearly impossible to comprehend. Today, that would be the bane of naivety and I would be laughed at out loud by nearly every school child with any remote sense of current affairs. We all sit and watch The Cobert Report or John Stewart’s comedy news and we take it in stride that our government is filled with idiots, charlatans and deceivers, but in the spring of 1974 the unfolding idea of that our president could be involved in orchestrating something as petty and foul as a break in of the Democratic National Headquarters seemed as reasonable as suggesting that aliens were living at Area 51 in Nevada. It was an odd time because the aftermath of the 60’s still came to bear and much of television was divided between the ostrich in the sand and confronting very directly, somewhat cynically and very much sarcastically the fact that all was not well with our society. All In The Family, Mary Tyler Moore, M*A*S*H, and Soul Train ran at the same time as The Waltons, Little House on the Prairie and American Bandstand. Children, even precocious 11 year olds weren’t capable of sorting out the cultural dissonance taking place at the time. Watergate, changed all that. It made real in a televised cultural way that our society was deeply corrupt at its core. There was no more room for a beautiful landscape of democracy that would self-correct. You knew, even then, there was no coming back from what was uncovered with Nixon’s dirty dealings. Sure, governments and centralized power are always prone to corruption, but what uncovered the deceit of Nixon was the fourth estate. Today there is no more fourth estate. Woodward and Bernstein would have been laid off by now.

I’m making this distinction between the fracture of a belief that I encountered in my youth back in 1973-75 and now because I think the monumental difference between the two eras is quite simply, back then there was a belief to begin with. It seems today that adolescents aren’t silly enough to believe our government works or that politicians are held accountable or even that what they see on television is reality, but rather that it is all a shifting landscape of available cynical gestures ready for the proverbial YouTube mashup. Authenticity is nearly dead and gone and what remains is mocked openly for it’s naive sensibilities and lack of adherence to the only remaining god, money. It should come as no surprise than, that our most culturally mainstream art form, television has created two powerful dramas that ooze of disdain and contempt for all things moral, righteous or truthful and that deny the concept of authenticity as a strategy, shouting its finality from their bully pulpit.

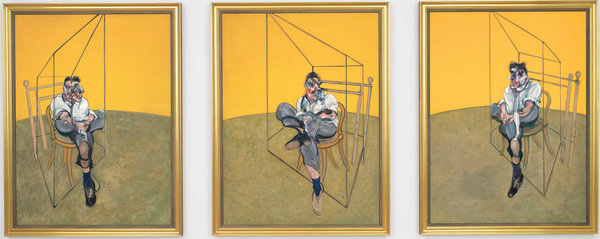

True Detective and the second season of House of Cards act as agreements in an argument with no contradictions. These dramas about police work in the heart of Louisiana and the machinations of our central government in Washington, DC, accept bleakness as religious doctrine. Both shows a denuded moral landscape so tangible it is like smelling a peach at the apex of its ripeness on a hot summer day. The fine art world, if we can any longer call it that, has remitted a similar ripe oblivion but exhibits it in a way largely inaccessible by the average American, let alone any real admirer of art. Matthew Barney’s latest plethora of shit (literally) filmic opera promises a more esoteric rendering of the aforementioned television dramas. But few will ever see Barney’s high fashion elitist rendition of scatalogical infinity, but many will see House of Cards and True Detective. The new dramas hint back to the fears of the 1970’s (nuclear war, the beginning of the AIDs plague, sexism, and government corruption from the top down) but instead offer a new outpost in post-postmodern explication that insists we should all make peace with the fact that all is lost, rather than remain firmly connected to any remnant of hope. At least, dare I say, there were rafts one could reach out for in the river of shit of the 1970’s. What make these new dramas even harder to digest is the fact that they are so profoundly well acted and written. There is no wink or nod to McLuhan’s Bonanza Land, as in David Milch’s magnificent Deadwood. House of Cards 2 and True Detective forego the Shakespearean rhetoric and ode to westerns in favor a unannounced punch in the nose. Thank you sir, may I have another.

True Detective and the second season of House of Cards act as agreements in an argument with no contradictions. These dramas about police work in the heart of Louisiana and the machinations of our central government in Washington, DC, accept bleakness as religious doctrine. Both shows a denuded moral landscape so tangible it is like smelling a peach at the apex of its ripeness on a hot summer day. The fine art world, if we can any longer call it that, has remitted a similar ripe oblivion but exhibits it in a way largely inaccessible by the average American, let alone any real admirer of art. Matthew Barney’s latest plethora of shit (literally) filmic opera promises a more esoteric rendering of the aforementioned television dramas. But few will ever see Barney’s high fashion elitist rendition of scatalogical infinity, but many will see House of Cards and True Detective. The new dramas hint back to the fears of the 1970’s (nuclear war, the beginning of the AIDs plague, sexism, and government corruption from the top down) but instead offer a new outpost in post-postmodern explication that insists we should all make peace with the fact that all is lost, rather than remain firmly connected to any remnant of hope. At least, dare I say, there were rafts one could reach out for in the river of shit of the 1970’s. What make these new dramas even harder to digest is the fact that they are so profoundly well acted and written. There is no wink or nod to McLuhan’s Bonanza Land, as in David Milch’s magnificent Deadwood. House of Cards 2 and True Detective forego the Shakespearean rhetoric and ode to westerns in favor a unannounced punch in the nose. Thank you sir, may I have another.

Maybe what bothers me most about all this acceptance of corruption, hate, violence, darkness and sexual malaise is the complacency around it. More than affecting a new kind of awareness, a call to arms that we should all recognize something is terribly amiss about our culture ala Network (1976), we are left alone in the dark to contemplate time being a “flat circle”. True Detective in particular acts as a model for the two extremes that represent themselves in modern America. On the one had we have the greatest increase in religious extremism and fundamentalism in our history, and on the other, the unraveling of time/space with the discovery of the Higgs Boson. I should be celebrating M-theory being used as an expository monologue in American mainstream television, but instead it just makes me sad. To hear Matthew McConaughey recite multiverse theory and superimposition betrays it the wonder it deserves despite his lilting Texas accent. Pizzolatto’s message is clear, we’re all rodents on an endless treadmill doomed to repeat ourselves. Similarly, Francis Underwood, played by the extraordinary Kevin Spacey (who reminds me there is still hope for acting after the death of PSH) has a similar take on time/space, except that his is beholding to only one ideal—power. For the Underwoods as DC power couple, even rape can be turned into a power grab ratings gambit. Even Camille Paglia blushes at Claire Underwoods coldness and calculation.

Maybe what bothers me most about all this acceptance of corruption, hate, violence, darkness and sexual malaise is the complacency around it. More than affecting a new kind of awareness, a call to arms that we should all recognize something is terribly amiss about our culture ala Network (1976), we are left alone in the dark to contemplate time being a “flat circle”. True Detective in particular acts as a model for the two extremes that represent themselves in modern America. On the one had we have the greatest increase in religious extremism and fundamentalism in our history, and on the other, the unraveling of time/space with the discovery of the Higgs Boson. I should be celebrating M-theory being used as an expository monologue in American mainstream television, but instead it just makes me sad. To hear Matthew McConaughey recite multiverse theory and superimposition betrays it the wonder it deserves despite his lilting Texas accent. Pizzolatto’s message is clear, we’re all rodents on an endless treadmill doomed to repeat ourselves. Similarly, Francis Underwood, played by the extraordinary Kevin Spacey (who reminds me there is still hope for acting after the death of PSH) has a similar take on time/space, except that his is beholding to only one ideal—power. For the Underwoods as DC power couple, even rape can be turned into a power grab ratings gambit. Even Camille Paglia blushes at Claire Underwoods coldness and calculation.

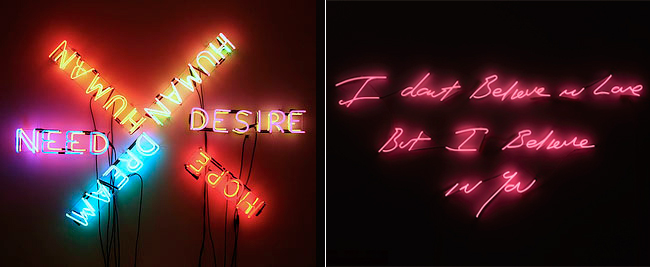

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JUfN8wL5zKY&w=560&h=315]I worry that we are less and less impacted, touched, and influenced by art and that it simply serves as yet another device to placate our boredom and hold hands as we walk the flat circle of time. Indeed, Barney’s River of Fundament, loosely based on Norman Mailer’s Ancient Evenings, is a nod to the perpetual flat circle of time. In some ways the current cultural dynamic is ancient in its parsimonious positioning of romanticism against cold pragmatism, but there is something deeper at play. We are regurgitating centuries of culture on top of itself to the point of blurring any recognition of origin or meaning. We are forcing end game thinking and you can see it in all the apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic art being made. This recursiveness will doom us to a self fulfilling prophecy if we can’t see something other, in effect, evolve. Where is the art that will evolve us? Where is the hope?