Art and the Artist

There is an age old question regarding the artist and the outcomes of that artist, namely can you despise the maker while still admiring what they made? Are there limits to that concept if the answer is yes? If the answer is no, is all art bound by its creator’s personality, and if so, what happens when the deeds of the human being have long since been forgotten but the art lives on? These questions seem to emerge more and more in an age when we are quick to judge people based on a perfidious text message or an off-handed comment that then goes viral. The diminishing privacy associated both knowingly and unknowingly around our social lives has only poured gasoline on the fire of moral boundaries. Although few traditional artists become celebrities, there work sometimes does. Few people knew who Chris Ofili was until Rudolph Giuliani decided to take issue with The Holy Virgin Mary. Aside from politicians feigning righteous indignation at artists to curry political favor, most so-called ‘blue-chip’ artists remain completely unknown by populist standards. What is known of these artists, if anything, is the product of their creativity, the art itself.

When art has an impact on a broad range of viewers it takes on a mystical association. Great art can be transcendent in it’s representations, providing the viewer with emotional responses that are otherwise the dominion of church, cosmology, philosophy or moments of extreme trauma or ecstasy. Natural human curiosity gets the better of us and we want to delve into how such a work was created and who was responsible for moving us so. Why else would a film like Gerhard Richter Painting even be possible? Although the film grossed a tiny amount in comparison to major film releases, (a meager $242,000 in the U.S.) none the less audiences sat transfixed as a german painter was filmed squeegeeing paint on and off canvases. The studio of Francis Bacon was dismantled, walls and all, after his death in 1992 and shipped to a museum in Dublin as if it were an ancient archeological relic. In the midst of this fascination about how an artists does what he/she does, lies the inevitable cult of personality. It isn’t enough to simply witness the act of art making, there is a desire to know the person behind it. What mind could create a great work of art? What is their behavior, their loves, their desires, their politics that inevitably fuel their production? Therein lies the rub.

Over the past three decades I’ve had the opportunity to meet, interact and sometimes even indulge in robust libation with a wide range of artists from MacArthur Prize winners and internationally renowned blue chip artists to complete unknowns. Given those experiences I can say unequivocally, that there is no secret sauce to making great art. Personalities range across the gamut of human beings from inglorious to generous. I have met artists of great stature that would blend into any local hometown diner unnoticed and those that carry such idiosyncrasies it is hard to imagine how they availed themselves to the world at all. On balance I would say that most artists are perplexed as much by what they do as those that view their art. They see their art making as a strange drive within themselves that they can no more shuck off than the shape of their head. Most artists create because they have an interior urge to do so. They are driven to share, in whatever strange way, their experiences both exterior and interior, of this world through the medium of their choice. It is precisely this ubiquitous urge that can create a dissonance between the art that is made and the artist who makes it. No artist in recent memory has met with more of this turgid dissonance than Carl Andre.

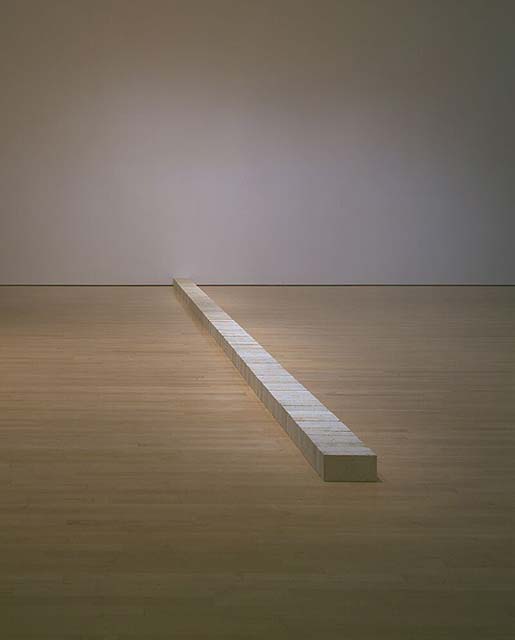

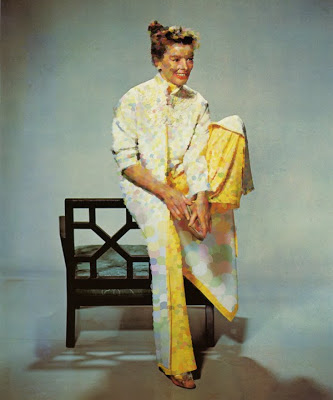

An enormous retrospective of Andre’s work just closed at the temple of all things Minimalism, Dia Beacon and it drew considerable attention and derision due to the personal life of the artist being represented. The reason for this is well reported and decades old, and carries the heaviest of moral weight with it; the death of another human being. On the evening of September 8, 1985 in Greenwich Village, New York, Ana Mendieta died by plummeting from the 34th floor of the tower in which Andre resided. The circumstances which led to her death are vague at best, particularly given the fact the only witness (or perpetrator) was Andre himself and both he and Mendieta were heavily intoxicated on champagne. Ana Mendieta was a rising star in the art world, albeit one who struggled against the shadow of Andre’s stature, her gender in a male dominated industry, and her Cuban heritage. It is precisely because of Mendieta’s heritage, gender, and politics that has attracted even greater attention to the incident, mixing with the few known facts to create a whirlpool of speculation, and passionate force. This can be heard in the Abstract Expressionist painter Howardena Pindell’s comment to a journalist just after Andre’s acquittal; “Oh, sure, I see it as totally symbolic: your life isn’t worth shit.” Thirty years on, Mendieta’s death remains a scab in the art world that reminds us of the inequality, and white upper class domination that dictates who is remember and who is forgotten. Many are wondering why, in light of the vagaries and loss of Mendieta, should Andre get such recognition now? Certainly, Dia Beacon feels as though Andre’s work is what matters and deserves, despite any whirlpool of discontent and anger about him as a person, deserved a retrospective.

Since the beginning of Carl Andre’s trial the confusion and sometimes contradictions in Andre’s portrayal of the circumstances combined with the fierce feminist community that Mendieta was a part of, has created a toxic mix of emotion. When the Dia Beacon retrospective opened, animal blood and guts were thrust upon the Manhattan location of Dia in an effort to draw attention to the still raw emotional wounds that remain with those who feel Mendieta was killed rather than fell. Although Andre was acquitted of the murder in a rare non-jury trial (he waved his right to a jury and asked that the judge be the sole decider of the outcome) many feel verdict was unjust.

When I read the plain style account Naked By The Window written by Robert Katz that wove together Andre and Mendieta’s past, as well as the known evidence and resulting trial, I felt confusion and discontent. It seemed entirely possible and plausible given Andre’s size, his level of intoxication and the volatility of his relationship with Mendieta that he could, in a moment of passion, have thrown her from his apartment window. The window sat above a hip-height (for Mendieta) radiator and it was well documented that Mendieta was terrified of heights. Making it even more difficult was Andre’s sometimes seeming bizarre behavior, sullen demeanor and his uniform of denim overalls. He went silent about the circumstances of the evening and he closed himself off from Mendieta’s family, some say in order to avoid moral judgement at a time of guilt. It took three grand juries to indict Andre to trial and the entire proceedings dragged on for three years creating an operatic arc within the tiny Soho art community that was the New York art world then. Artists like Frank Stella, a life-long friend of Andre’s still finds himself the point of criticism for immediately putting up bail for Andre when arrested. Rich white men, protecting other rich white men, the saying goes. This opera has persisted and aside from the verdict, and unresolved (and likely forever unresolved) circumstances of Mendieta’s death, it is exacerbated by the the type of work that Andre creates—Minimalism.

It has been reported that at the time of Andre’s trial, the art bar Puffy’s passed a pitcher with “CARL ANDRE DEFENSE FUND” written on it and someone put a brick in it. Minimalism remains to this day one of the more unpopular art movements, despite its universal philosophical themes. Since its inception in the 1960’s it has been derided as both overly simplistic (a tired and common argument used against art) and as a cold embrace of latent modernist principals. The fact that Andre became powerful within the art world by aligning standard construction bricks on a floor in classic geometric patterns adds to the fury against the man and his work. Like many artists of that period he is both a heavy drinker and averse to discussing the art work itself. The few times Andre has spoken about his work or art making it only adds confusion or contempt toward his personality such as, “I mean, art for art’s sake is ridiculous. Art is for the sake of one’s needs.” Position this quiet, middle-aged, wealthy, white male who was dominating the art world against the fiery, Cuban Mendieta whose work was powerfully grounded in themes of feminism, identity and mysticism and you have the perfect storm of binary fracture—women versus men, color versus white, body-centered art versus material Minimalism, outsider versus the establishment. This dynamism has muddied the waters related to Andre’s retrospective no matter what side you fall on, guilty or not guilty in terms of Carl Andre the human being. On the second to last day of the retrospective at Dia Beacon, several women artists staged an event called “CRYING; A PROTEST” where they walked amongst Andre’s works and began crying for the loss of Mendieta and her absence from the exhibition. My friend Faheem Haider, also wrote about the lack of acknowledgement of Mendieta in the retrospective and suggested that the man, Carl Andre was hiding behind the work in order to avoid responsibility. If one is responsible to universal principals, Faheem suggests, then he might feel it unnecessary to address things on a day to day scale.

The death of another human being by mysterious circumstances, especially one of such promise and creative power is incredibly difficult to anneal. The fact that Mendieta and Andre were such opposites also attracted to each other only makes the mystery and tragedy of her death more ripe and volatile. There remains the question, outside of the tragedy, of whether or not Carl Andre’s work should be given the attention inherent in a retrospective? Can the work be viewed for it’s aesthetic value outside of the conditions of Andre’s personal life? If a retrospective is warranted, despite the tragedy, is it necessary to include mention or representation of Mendieta’s work? I think it’s important to keep in mind at such contentious crossroads as these, that one of the functions of art, if it has a function at all, is to present ideas that scratch at the underlying components of our humanity. There is no right or wrong approach to that practice and much of art is oblique, raising more questions than answers. In my mind it is hard to argue against the body of work that Andre has produced in his lifetime and the contribution it has made to art as a conversation about humanity. You may hate it’s overt simplicity, its ground in the Tao Te Ching or what you perceive to be a love of modernism’s power, but the impact it has had and influence on art and everyday life is hard to deny. Minimalisms influence, for better or worse can be felt all the way down the line to the design pornography of Apple. Is it a horror that Mendieta was taken from us, no matter the circumstances so young—of course. Her voice in the art world today is much needed in a dynamic hell bent toward commodity and consumerism. The loss of her future contributions to art is a loss for all of humanity.

L. Carl Andre, "Grecrux" (1985) - R. Ana Mendieta, "Silueta Series, Iowa" (1977)

There is a long line of art production that has been made by terrible people or born out of societies terrible in their actions. Should we condemn Mayan art or Egyptian art because of the behavior of those cultures? Should all of the armor be removed from museums throughout the world because it was created for the purposes of war, no matter how beautiful? Should On the Waterfront be permanently banned because its author, Budd Schulberg sold out others in Hollywood to the House Un-American Activities Committee, often destroying their careers? Does it make On the Waterfront any less of a powerful story? I believe it is possible to separate the local human dimensions of an artist’s life from the work of the artist. Many artists cannot explain how it is they do what they do or even how their better works came into being. Impulse, instinct, drugs, passion and every other thing that is uniquely human creates a conflagration of ideas and actions that becomes a work of art. Artists often refer to it as the happy accident. When the outcome of that is something that can move us either in anger, disgust or in ecstasy and joy, the artist has done their job, even if that artist themselves is lousy at living.

One way that Dia Beacon could have dealt with the emotionally charged atmosphere surrounding Carl Andre better, would have been to dedicate space and energy to a dual retrospective of Mendieta’s work. The fact that her work was an offshoot related to Minimalism could have been creatively curated in a way that both recognized the tragedy of her death as well as the likely underlying reason she came to fall in love with Andre, and visa versa, to begin with. An institutions job is ultimately to give a platform to the artists who have had a memorable impact on the human story. A combined retrospective of the two artists would have not only been deserved on both parts (who knows where Mendieta would have taken her land-body art practice) but would have given a meaningful frame to why art is important to begin with.