Barnett Newman’s Heroic and Sublime

“I hope that my painting has the impact of giving someone, as it did me, the feeling of his own totality, of his own separateness, of his own individuality.”

—Barnett Newman

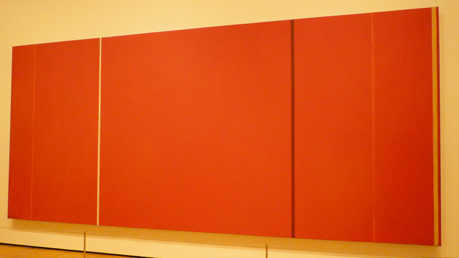

It is not an accident that Barnett Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis hangs in direct opposition one room away from Jackson Pollock’s One: Number 31, 1950 at the Museum of Modern Art. These are the iconic art works of 20th century modernity. Each of the rooms at MoMa is a mirror of the other, an alternative reality. Each room contains a large soft bench where you can sit and loose yourself in these works. I often imagine the lights dimmed with only spots on these two paintings and large recliners set up to view them. They were the flat screen televisions of their time. The men who made them hoped for them to represent something much larger — our connection to the sublime. In the 21st century the boundaries of our physical existence are less and less clear. We live in a virtual cocoon, separated from our heroic selves by the devices that simulate reality. Our experience with color, for example is primarily through reproduction on the internet or in prints in books. Even when traveling in our exterior environments we immerse ourselves less and less, preferring instead the cloistered canister of the automobile and its tinted, UV filtered windows. The bench in front of Vir Heroicus Sublimis is there not as a relief from walking, but a gentle suggestion to sit, slow down and allow us to meditate on Newman’s seventeen foot wide painting and what it means to us in this world of the simulacra.

Barnett Newman’s paintings are not elegies, narrations or allegories. His work was a descriptor of the basic relationship of human beings to our own unconscious. We are reductive, categorical, selective and analytical animals. We invented binary code, ones and zeroes now responsible for the entirety of our global communication. Newman’s invention of the “zip” was just that — an elegant gesture which allows the viewer to look not at the ‘object’ of the painting but into their own personal narrative. It is both a linear disruption of the horizontal plane (as architecture is against the landscape, for example) and a metaphysical meter; a stroke of time or note on an instrument. As Newman perceived it, it was a heroic gesture. Man’s insinuation on the landscape as the hero of modernity, the master of his universe and creator of the sublime. Newman wasn’t interested in wrestling with his inner demons and revealing the psychological underpinnings of our existence as Pollock was. No, Newman saw glory in our purpose as humans and modern painting would be the symbolic relic of our technological superiority.

Despite Newman’s glorification of man’s heroic tendencies in a post-war America, the emergent consumer culture of the 1950s was largely baffled by his work and most Americans remain so today. What Newman understood long before our current idiosyncratic hyperactive culture was that the essence of humanity, the basis for our difference from the apes, was our ability to confront the existential. Newman was a painter and he saw a new way to say something by reminding us of our own divine purpose our heroic urge. When we gaze at the night sky we can choose to see white dots of light against black sky or the endless variety, density and complexity of a universe largely unexplored. The “zip” is symbolic, a ripple in the still pond, a line on the pavement or a word that breaks an uncomfortable silence. It is also the disruption, for better or worse, of mankind’s technological development. Newman recognized we were replacing the idea of the religious sublime with the technological sublime. The “zips” are programmatic, wether by God or man, their meaning is locked in the software of truth.

Newman used painting to describe, decades ahead of his time, our relationship with technology and the duality of our metaphysical and physical lives. Why do some devices, some technologies grab the collective conscience and others don’t? What is it about the iPhone, for instance, that connects with us in ways that other forms of technology do not? The answer is ambiguity, the least likely of our possible responses. It is not in the object which lies our desire, but rather, the object acts as the gateway for our own imagination. Barnett Newman’s paintings addressed issues key to modernity; scale, color, simplicity and geometry. These paintings were architectural in nature. The aftermath of the second world war left America the sole interpreter of modern culture. The architects of the time chose to represent that as hubris, the painters as epiphany (another kind of hubris). Newman among others, used the scale and geometry of architecture in conjunction with the color and line of painting in order to transcend our ideas of the object in the same way we forget the iPhone is an object. Painting to Newman, was heroic without signifying a singular hero. It empowered everyone by allowing them the contemplative space to produce their own ideas. What Newman chose not to see, in contrast to Pollock was the inevitable destructive power of the myth of the hero. He embraced the idea that programmatic thinking was a gateway to the sublime without taking responsibility for the software. The red in Vir Heroicus Sublimis represents glory, life force and the intensity of vision not the color of violence or the blinding center of a thermonuclear reaction. What we are now very slowly discovering is our own ‘heroic’ tendencies and blind embrace of technology may very well be our own undoing. As Peter Sloterdijk says in his new book, Terror from the Air; “Modernity conceived as the explication of the background givens thereby remains trapped in a phobic circle, striving to overcome anxiety through technology, which itself generates more anxiety.”

Wether programming (software) or “zip”, painting or flat screen television, we must be cautious of the draw toward the heroic. Technology allows us personal access to an elegance similar to natures. We are enticed by elegance because we intuitively know the extraordinary, the profound, lies hidden in plain site beneath the black mirror surface of a lake or beyond the twinkling stars in the night sky. We are drawn to mimic what defies our understanding in the hopes of gaining that knowledge. Newman’s brilliance was leveraging the physicality of pigment on surface to reconstruct the metaphysical of the mind’s understanding of its universe. Georges Didi-Huberman, leveraging themes from Walter Benjamin says in his description of Newman’s paintings; “We must seek to understand how a Newman painting supposes — implies, slips underneath, enfolds in its fashion — the question of the aura. How it maneuvers the ‘image-making substance’ in order to impose itself on the gaze, to foment desire. How it thus becomes ‘that of which our eyes will never have their fill’. Newman’s paintings remain relevant today because they give us the opportunity to question technology through the very questions Benjamin suggests. We can see in Newman’s painting the reductive embrace of the programming that has led to the narcissistic embrace of our own inventions. We impose our own narratives on devices such as the iPhone. The narrative of our lives as lived through the virtual connection the device gives us to our friends, colleagues and indeed the world. It should not, however, be mistaken for knowledge of any of the above. To dismiss Barnett Newman is to deny our grappling with the heroic, the metaphysical and our own narcissism. Narcissism is a denial of uncertainty and therefore a denial of a larger truth. What Newman can teach us, if we choose to take a seat on the bench, is our own dark desires. The very heroic impulses that led us to develop the personal computer, the cell phone and the internet are the very same that annihilated Hiroshima & Nagasaki, and pumped enough CO2 into the atmosphere that we have irreparably altered the global environment. Heroic indeed.